When death came to Samara

Photographic evidence of famine engulfing the Soviet Union moved the public to donate.

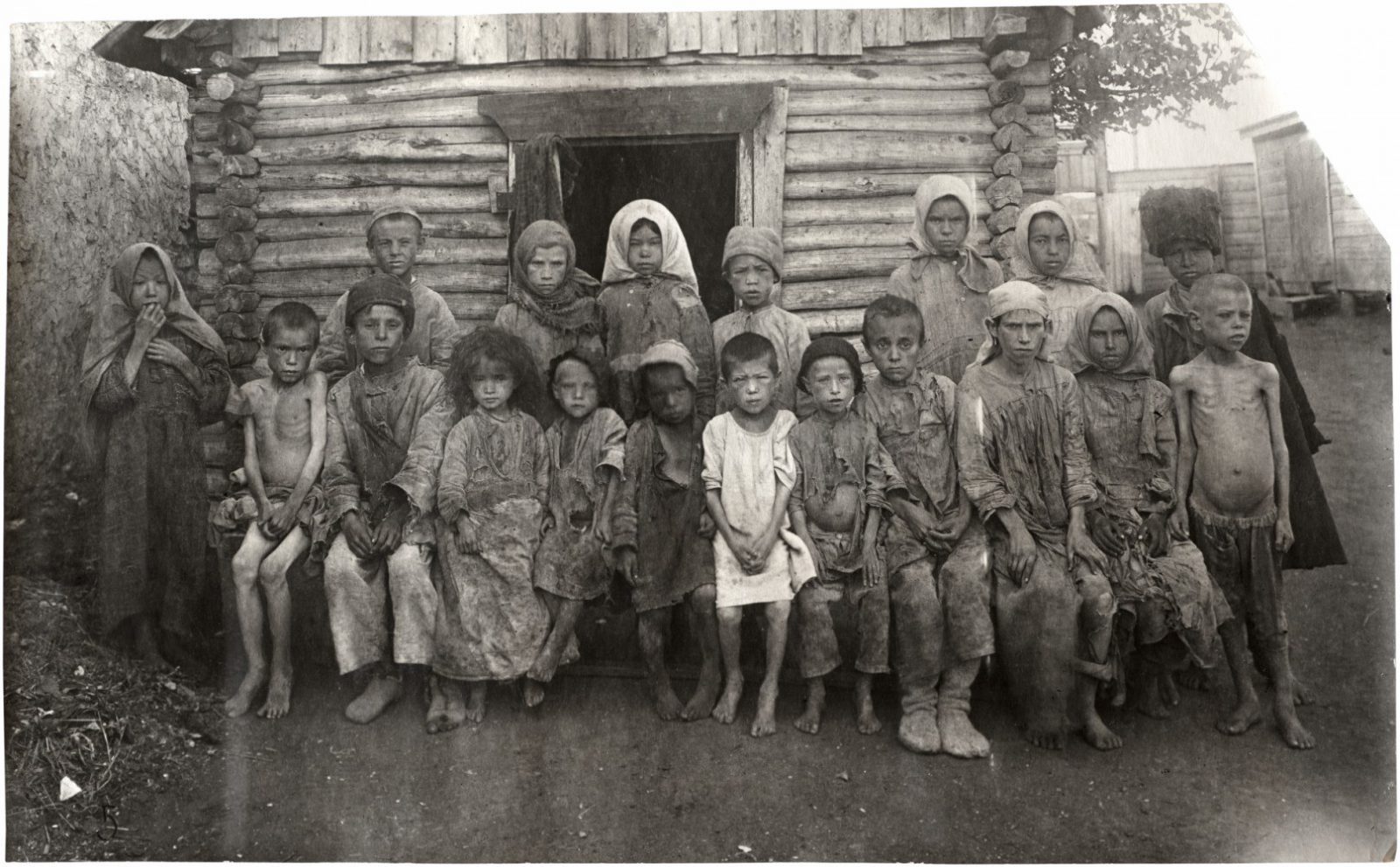

Hunger descended on the fertile banks of the Volga River in early spring 1921. Civil war, food requisitions and a severe drought all contributed to the terrible famine that would grip the region until 1923. With no other food available, people would eat their domestic animals, including cats and dogs, wild grass and even the reeds used to build their thatched roofs. Desperation grew and instances of cannibalism were recorded. The region’s villages were abandoned, as starvation drove people out of their homes in vast numbers.

It is estimated that the disaster affected more than 30 million people of which 5 million perished from hunger.

In late summer 1921, two extensive international aid operations swung into action. Herbert Hoover, who would later go on to become president of the United States, led the operation by the American Relief Administration (ARA). A second, smaller, humanitarian operation by the International Committee for Russian Relief (ICRR) was led by the Norwegian explorer and diplomat Fridtjof Nansen. In 1921, he had been appointed the League of Nation’s high commissioner for refugees.

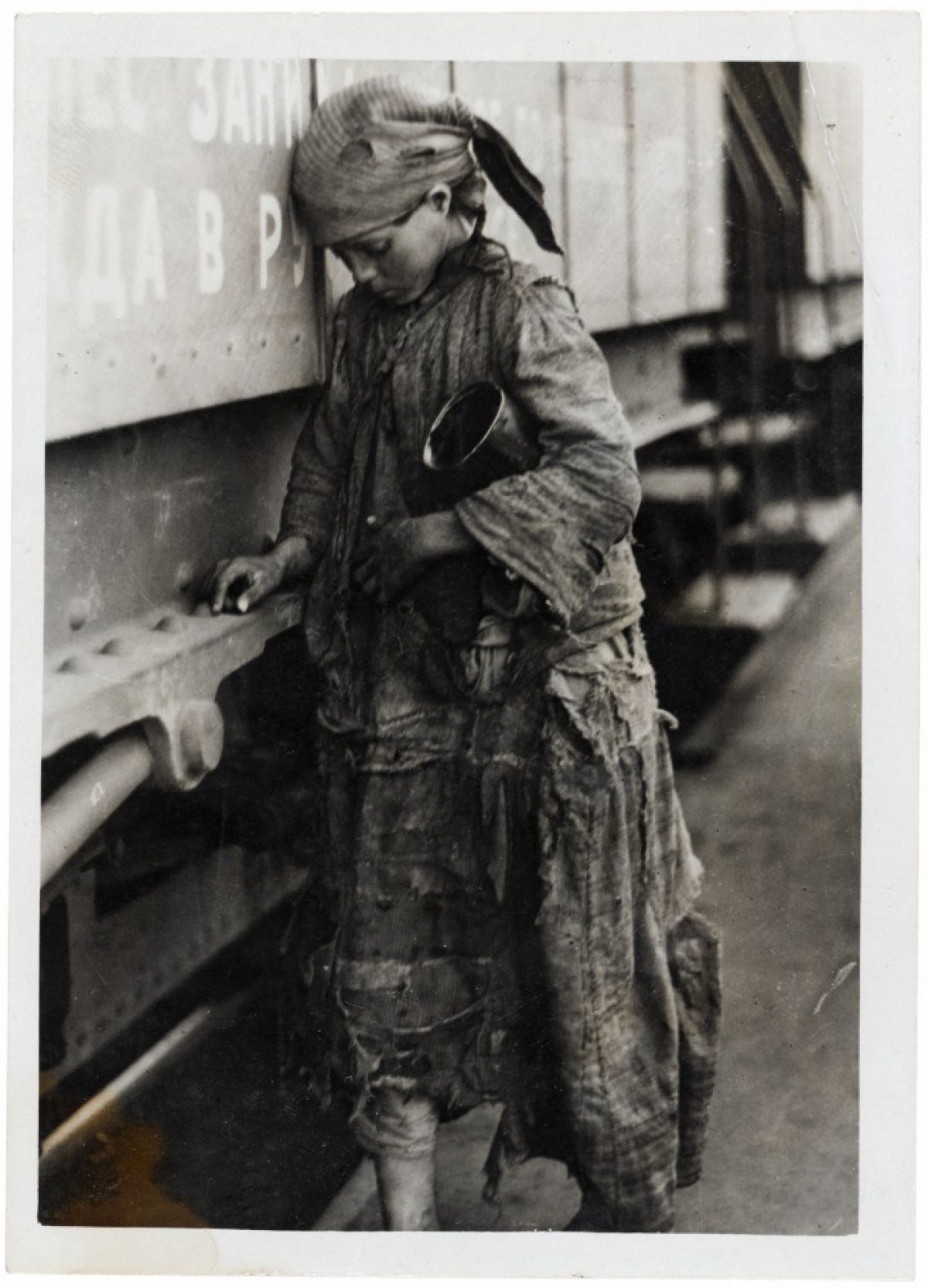

Later that same year, Nansen and his crew travelled to the Volga region to gain a first-hand understanding of the unfolding catastrophe. After his return, he began a fundraising campaign in Europe and the United States. He had the insight to appeal to both governments and the general public by showing them photographs taken in the disaster-hit region. The photographs were shown in exhibitions, published in newsletters and turned into posters and postcards. The horrific images shocked their audiences and were a great help with fundraising efforts. The Nansen Mission comprised more than 30 international organisations, including Save the Children, Red Cross and the Quakers. In 1922, Nansen was presented with the Nobel Peace Prize in recognition of his humanitarian relief work.

Hundreds of Nansen’s aid workers travelled to Russia between August 1921 and 1924 to distribute food, medicines and clothing to those caught up in the famine. One of them was Grigori Grigorjevitš Aleksandrov (1886–1937), a Russian theatre director and doctor.

In 2006, Aleksandrov’s granddaughter Mirjami Niinimäki discovered 64 photographs among her grandfather’s estate in Sweden. Of these, 36 had been taken by Isaiah Liberman, a Samara photographer, with a further two credited to V Ja Mozhejko, another local man. The other photographs are unattributed. Despite their poor condition, the photographs reveal the hopelessness and despair of the people in the Volga region in 1921–1922. Some of the photographs have been glued onto a cardboard sheet, suggesting that Aleksandrov, too, was involved in organising photographic exhibitions to raise funds for the relief effort.

The photographs show farmers wearing little more than rags, starving, bedridden people, groups of orphans with distended abdomens and little in the way of clothing, shoes or socks, half-naked, emaciated children, mothers on the road fleeing hunger, abandoned houses, frozen bodies piled high at a cemetery, body parts dismembered for eating.

Photographs from Aleksandrov’s collection were published in the Suomen Kuvalehti -magazine in February 2019. Aleksandrov’s granddaughter gifted the images to the JOKA press photo archive in 2022.

Text: Raija Linna

Kamera 6/2023

Buzuluk cemetery in Orenburg, winter 1921–1922. Photo: Otavamedia / Press Photo Archive JOKA / Finnish Heritage Agency.

Girl collecting seeds, Samara railway station, 17 August 1921. Photo: Otavamedia / Press Photo Archive JOKA / Finnish Heritage Agency.