A total work of art

Artists’ portraits from the press photo collection of the Otava publishing company.

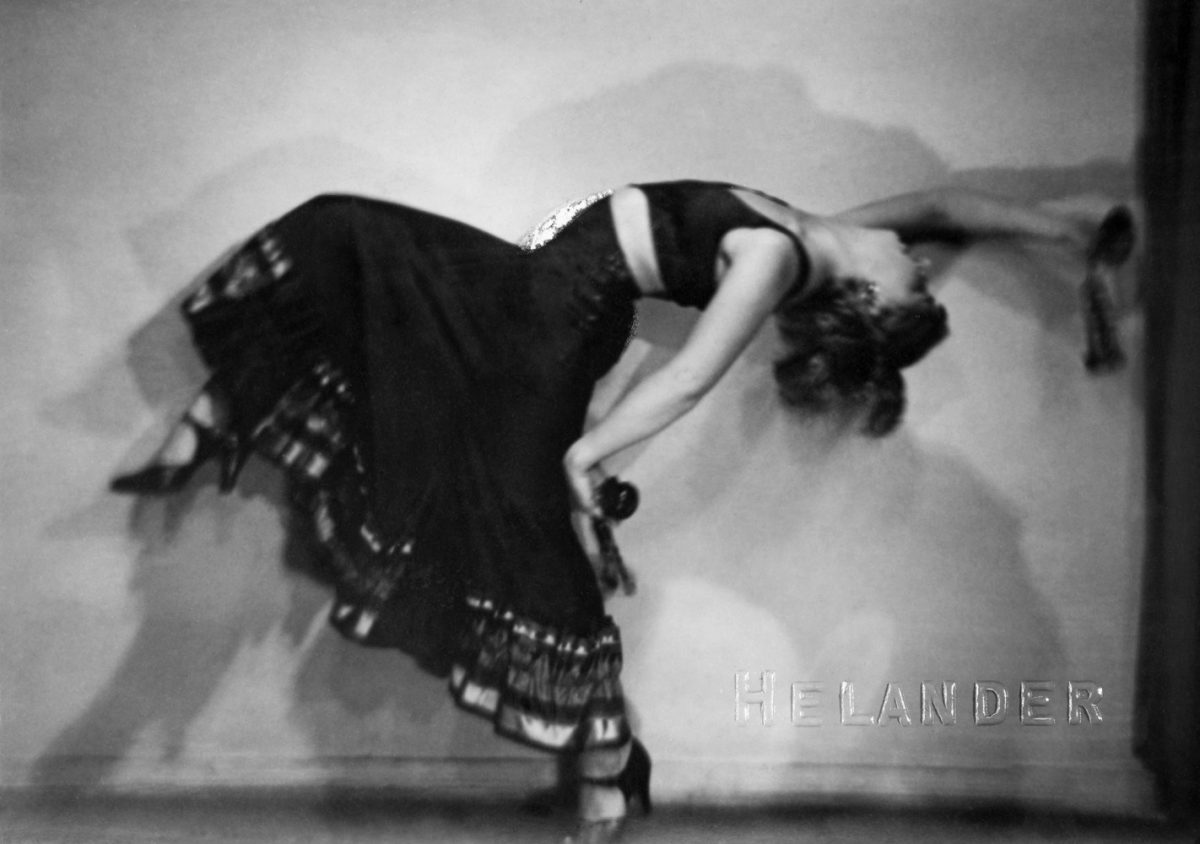

The press photo from the Suomen Kuvalehti magazine shows dance artist Martta Bröyer performing in Helsinki in 1933. The dramatic bend blurs the body’s outlines, which seem to be doubled in the shadow of the backdrop. The impression of the movement brings to mind the swirls of music and a cinematic setting. The photo becomes the physical dance of light.

The idea of a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art, is a key part of a modernistic approach to art: the elements of various forms of art, such as music, drama, visual arts, poetry and dance, are combined. Composer Richard Wagner presented this term in his 1850 essay The Artwork of the Future: a total work of art was an “artwork of the folk upon the public arena of political life.” The boundaries between the audience and the performer and of art and life are fluid. The idea can also be seen in the trends of contemporary art, such as performance and body art. From the beginning, the idea also included a political aspect as the boundaries of art expanded towards production and society.

Martta Bröyer was a dancer, reciter and choreograph. She studied in Europe to learn e.g. the eurythmic method of the musical pedagogue Emile Jaques-Dalcroze, in which music was studied through physical exercise and movement, not through theory. Bröyer invented her own form of art that combined recitation and movement. This form premiered in the ‘Dramatic Series’ shown in Helsinki in 1927. Bröyer taught her method for 45 years. For a long time, she lived in her childhood home in the Ruiskumestari building in Kruununhaka, Helsinki, which she sold to the City of Helsinki in 1974.

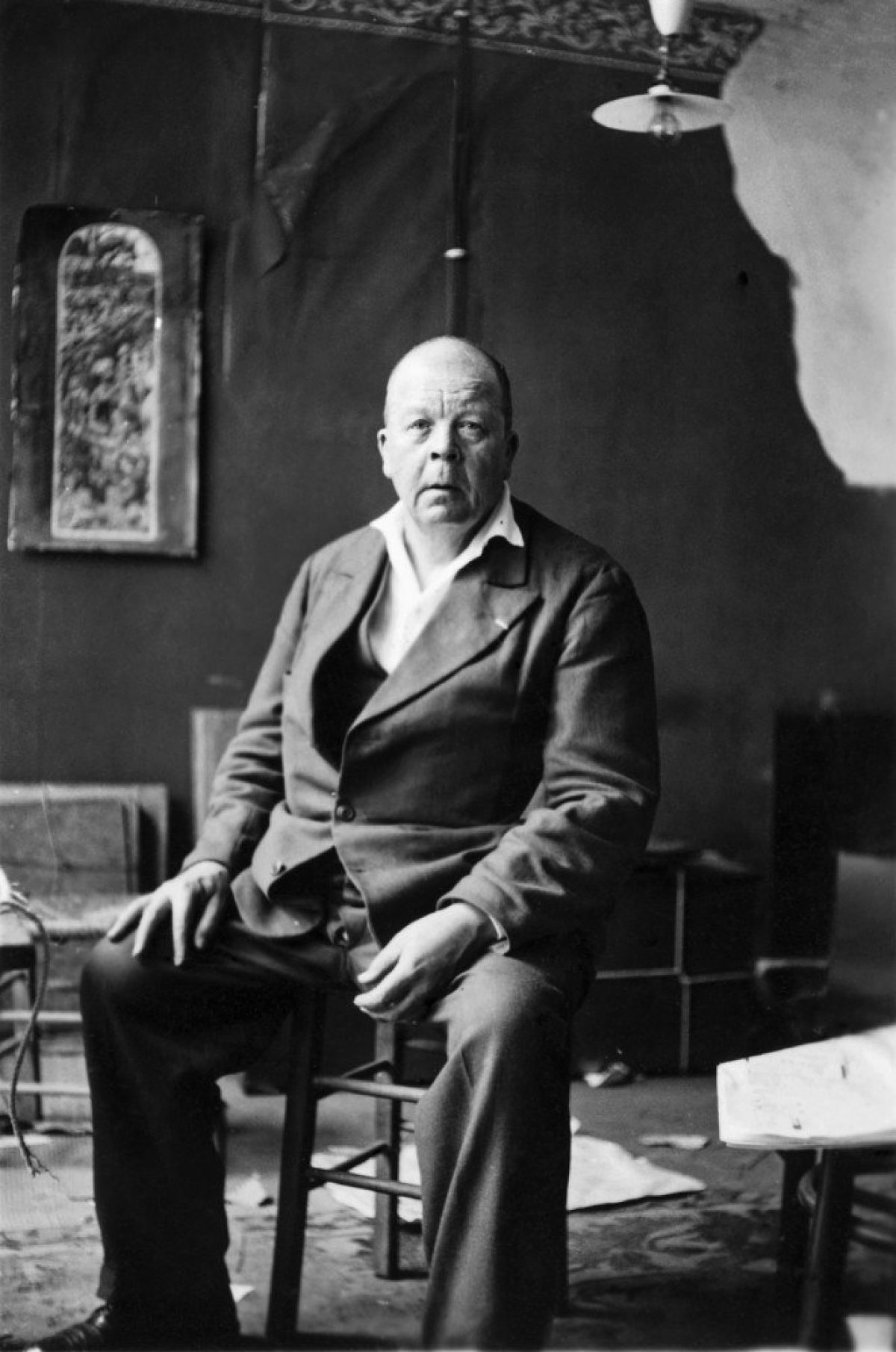

The idea of the total work of art is also represented in the central piece made by painter Juho Rissanen late in his career: the stained glass triptych by the stairwell of the Bank of Finland (1933). After becoming independent, Finland started to build its national identity, and in the 1920s the monumental works of art in state premises were seen as more valuable than individual paintings or sculptures. Rissanen made use of his layout skills and the bright colours of modernism when matching the painting with the architecture. Light was filtered through the stained glass installation as visitors moved about the ‘national stage’ of the Bank of Finland’s stairwell. Journalist Ada Norna talked to Rissanen in Paris when the finished works of art were about to the delivered to Finland. Rissanen said the triptych was intended to “signify from where money is coming to the Bank of Finland. I put agriculture here in the image of harvest, connected export industry to log driving, and the Helsinki Baltic Herring Market as a presentation of trade.”

Ada Norna was the correspondent for the Uusi Suomi magazine in Berlin who also aided Suomen Kuvalehti. In the 1930s, she had a positive view of National Socialism and had close ties to the propaganda machine of Nazi Germany. This ensured her access to the main stage of the Nazi ideology, the march and flag performances in which the German identity was produced “in a work of art, through a work of art, as a work of art.”

Text: Inkamaija Iitiä

Kamera 8/2021

Artist Juho Rissanen in Paris in 1933. Behind him, you can see a draft of the piece called ‘Log Driving’. Photo: Otava / Press Photo Archive JOKA / Finnish Heritage Agency

Studio Helander: Dance artist Martta Bröyer in Helsinki in 1933. Photo: Otava / Press Photo Archive JOKA / Finnish Heritage Agency