In the lands of the Mansi

Linguist Artturi Kannisto in Siberia in 1901–1906.

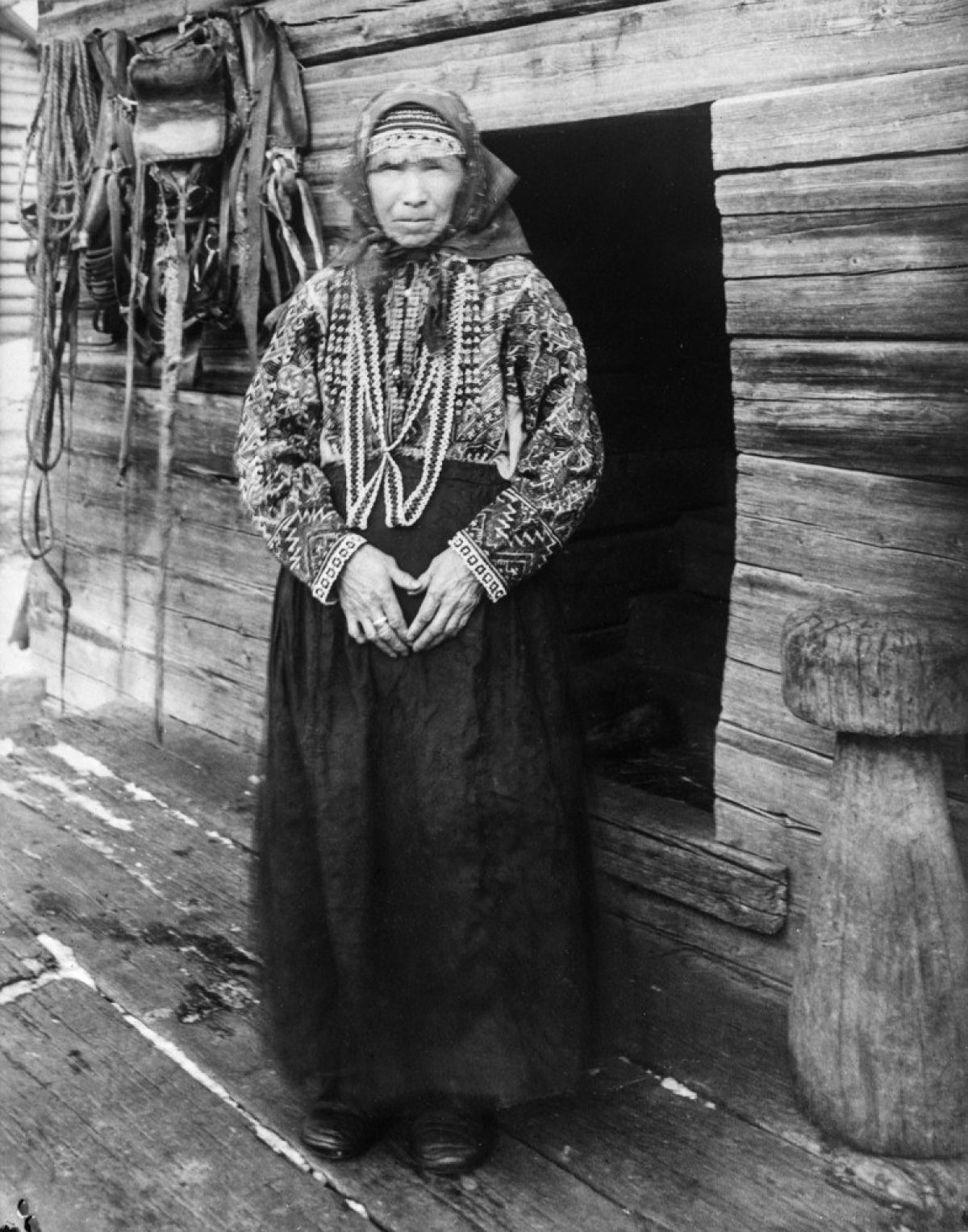

Before the First World War, the Finno-Ugrian Society sent dozens of researchers to visit the Finnic peoples. Since the expeditions of August Ahlqvist (in 1858, 1877 and 1880), no Finnish linguist had visited the lands of the Mansi (the Vogul). The Society saw that it was important that the research on the language and folklore of this dying people would continue. At the turn of the century, there were still 10,000 living Mansi, but the Russification of the southern parts of their home region was already heavily underway. The Society chose Artturi Kannisto to go on an expedition.

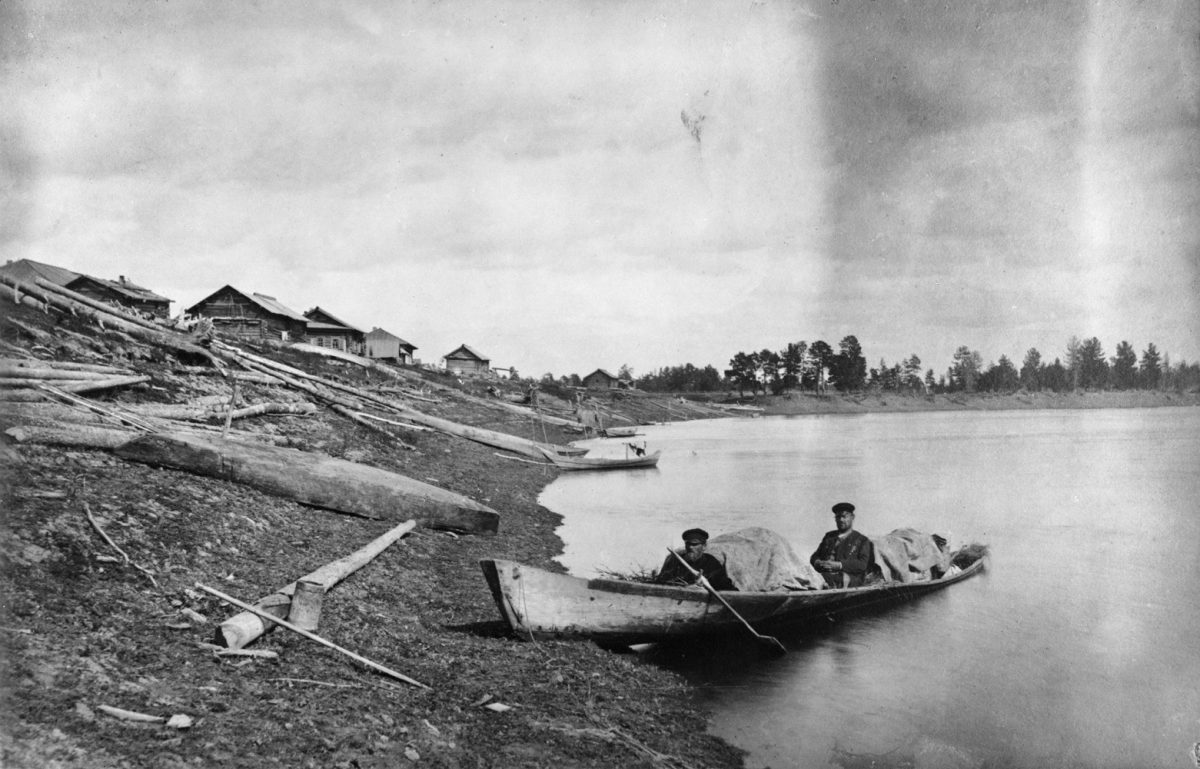

Kannisto travelled to the governorates of Tobolsk and Perm in Russia to live among the Mansi. He stayed there from 1901 to 1906. In the beginning of his journey, Kannisto acquired convincing referrals and letters of appointment for himself since both the officials and the common people in Siberia were suspicious of all visitors. Depending on the season, he travelled by either sleigh or boat, and traversed over 4,000 kilometres.

Kannisto’s main mission was studying the language of the Mansi. Of all Finno-Ugric languages, Mansi was closest to Hungarian. It has been proven that in about 1000 BCE, the ancestors of the Hungarian, Mansi (Vogul) and Khanty (Ostyak) peoples formed a united horseriding population in the steppes south of the Ural Mountains.

Kannisto’s second goal was documenting the conditions in which the Mansi lived. The Mansi’s traditional livelihoods included hunting, fishing and reindeer husbandry. Raising cattle was establishing itself in the southern areas to a small degree, and the southernmost Mansi also cultivated land.

They worked long days: from eight in the morning to nine in the evening, Kannisto worked with a language master who spoke Mansi as his native language. They only stopped working for a short while to eat and drink tea. The conditions were extreme. In an article in the Päivälehti newspaper on 11 June 1903, Kannisto describes his night in a hut covered with reindeer skins: “Staying in such a hut overnight is not very pleasant for those not used to it. Your feet tend to feel cold even when wearing felt boots, and when you wake up in the morning, the first thing you do is thaw your beard to get it out of your collar.”

Kannisto enjoyed his time with the Mansi. They treated ‘the official sent by the Emperor’ with respect. He managed to gain their trust. In his letter to his sister in 1902, Kannisto writes: “Another matter is the Vogul’s distrust ... But I have gained so much trust among them that they have let me watch and photograph their sacrificial ceremonies.”

A great amount of materials to be delivered to Finland was collected during the expedition: about 30,000 notes of words from 11 dialects, folk tunes recorded on wax cylinders with a phonograph, objects, photos and various information to be archived (such as the number of Mansi in each village).

Photos by Artturi Kannisto (1874–1943) and pictures of the items he collected are available at www.finna.fi and www.museovirasto.finna.fi.

Text: Jaana Onatsu

Kamera 5/2021

A Vogul woman in a peasant dress. Photo: Artturi Kannisto 1905–1906 / Picture Collections of the Finnish Heritage Agency

Downstream of the River Lozva, on the way back from the Perm region. Photo: Artturi Kannisto 1903 / Picture Collections of the Finnish Heritage Agency