Organic travels in Lapland

UA Saarinen took photos on Ylläs before the era of ski lifts.

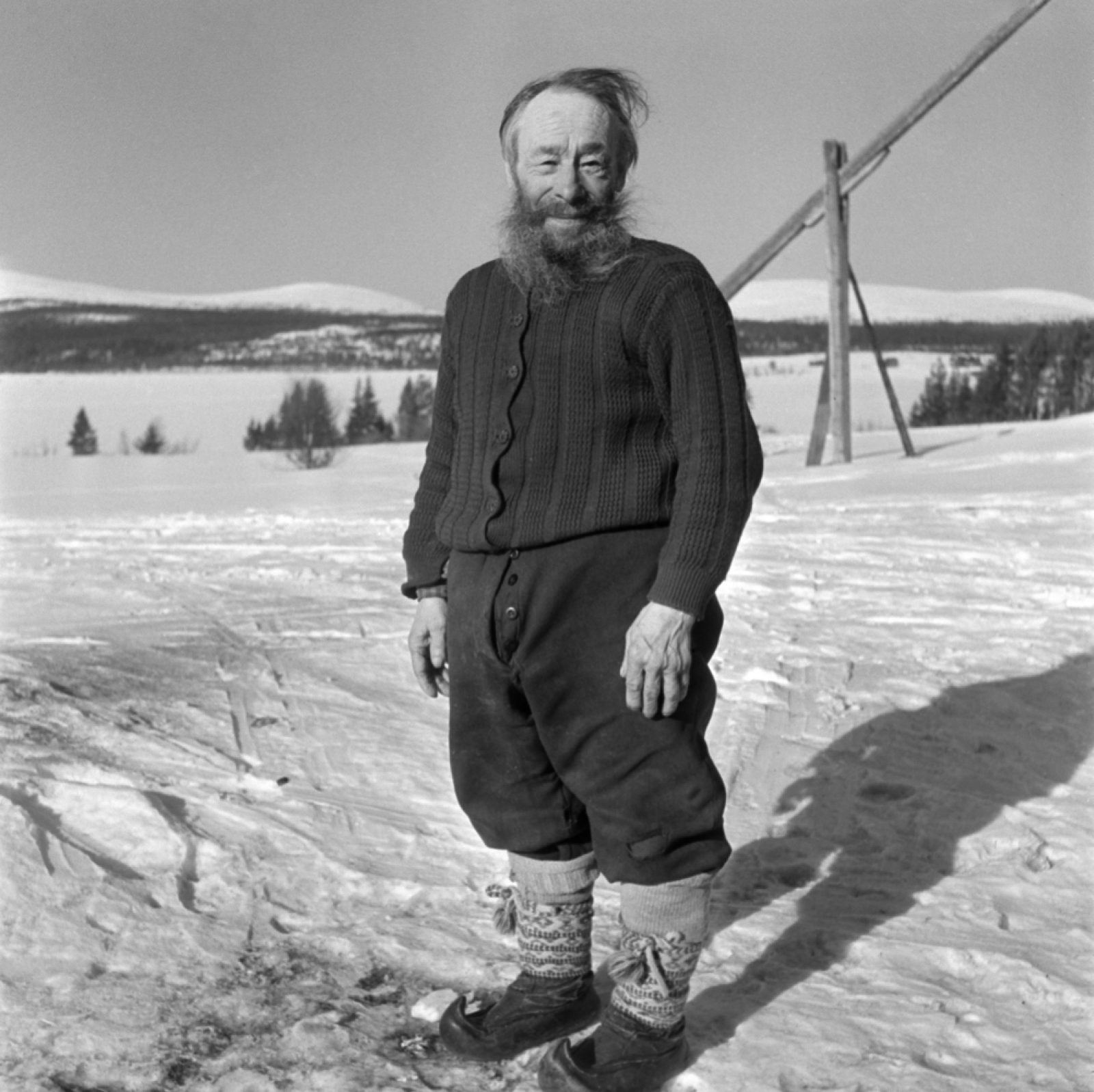

This is Karhu-Kustu, a man who has caught nine bears! An old guy with reindeer hind boots, his trouser buttons undone and beard blowing wildly in the wind.

I am looking at one of UA Saarinen’s photographs in the Finnish Press Photo Archive JOKA. I had seen the same picture the previous week during my skiing holiday to Äkäslompolo while skimming through my cabin’s guest book. The picture was taken 65 years ago.

Karhu-Kustu, a.k.a. Hannu Kustaa Äkäslompolo, lived in the village of Äkäslompolo, next to the Ylläs fell, in 1872–1960 and made his living by hunting and fishing. People also called him Pikku-Kustu, ‘Little Kustu’, as he was only 150 cm tall.

Karhu-Kustu used to shoot his quarry with a single-shot weapon, until his sister, Hedvig, sent him a Winchester riffle from America. The new weapon could be fired several times before needing reloading.

UA Saarinen took a winter holiday trip to Äkäslompolo at Easter 1954. I found some of his photographs on the Äkäslompolo family society’s website, where the people in the picture are accompanied by names and stories as part of the village’s history.

When southern travellers discovered Ylläs in 1934, the journey from Helsinki to Äkäslompolo took more than a day. The railway line ended in Kaulinranta, Ylitornio, and from there you had to take a coach to Äkäsjokisuu. The final 27 kilometres to Äkäslompolo had to be tackled on skis. It was not until 1953 that Äkäslompolo became accessible by road year round.

The villagers would offer holidaymakers accommodation in their homes. Cardboard and curtains were used to separate a section of the main room for guests. After World War II, nearly every house had guests staying during the winter holiday season, and women would tend, not just to their children and cattle, but to tourists as well.

Initially, accommodation bookings were made with postcards, but in 1954, the magazine Suomen Kuvalehti reported that ‘one of the village of Äkäslompolo's two phones is maintaining contact with the civilised world.'

Downhill skiing was a completely new thing for many. It was referred to with words describing a zigzagging motion. Ylläs received its first ski lift in 1957. Before that, the hill had to be climbed either on foot or with a reindeer. Reaching the top required considerable effort. Lapland was a new and exotic travel destination, and UA Saarinen managed to sell many of his pictures to Suomen Kuvalehti.

Saarinen, who was boarding with the Kurkkio family, wanted to capture an image of a genuine Sámi boy. The family's son, Markku, was dressed in an adult man's Sámi jacket, which was far too big for him, and a traditional Sámi hat borrowed from the neighbours, which was far too small.

The picture of Markku and a reindeer named Musta was published in Suomen Kuvalehti on 24 April 1954. From there, it started spreading. It first ended up on a poster at a travel fair in Germany, then in an American magazine and finally in a geography textbook in America.

An Alaskan school class sent post to Markku. They had glued his picture on top of the envelope and written ‘Markku and Musta, Lapland, Finland.' The postal services brought the letter to the newspaper Pohjolan Sanomat, whose journalists started looking for the intended recipient with the help of the picture. Thankfully, the Kurkkio family were amongst the newspaper's subscribers, and thus the letter from Alaska found its way to Äkäslompolo.

Raija Linna

Kamera 2/2019

Markku Kurkkio posing for UA Saarinen in 1954, wearing a Sámi outfit that is too big for him and a hat that is too small. Photo: UA Saarinen / JOKA / Finnish Heritage Agency (JOKAUAS2_1B01:4)