Witnessing the antics of a daredevil reporter

UA Saarinen captured reporter Matti Jämsä’s stunts on film.

Matti Jämsä (1929–1988) began working as a reporter for the Apu magazine in 1952. It was the final year of war reparations. The Olympic Games were held in Helsinki, and Armi Kuusela was crowned as Miss Universe. The people’s standard of living was slowly beginning to improve, and the hard times were making way for new, more enjoyable experiences.

As a young man, Jämsä created his own story genre, in which he was both the author and experiencer. In the 1950s, television was still new and the culturally uniform Finns yearned for entertainment.

Matti Jämsä’s reports were read with great enthusiasm. His stories were often published in two parts. Jämsä never hesitated to explore life’s various avenues and conduct risky experiments: Jämsä as a newsagent, homeless Jämsä, Jämsä drives a car into the sea, Jämsä as the theme park mermaid in Linnanmäki. These stunts attracted a lot of attention, and people would contemplate whether Jämsä was going to survive his experiments.

UA Saarinen (1927–1991), a news photographer a few years Jämsä’s senior, captured many of Jämsä’s stunts on film. One of these stunts was a trip from Turku to Stockholm on skis and a rowing boat in 1954.

The two men intended to travel along an old postal route and discover how difficult it had been in the olden days to carry mail. In early March, spring was on its way and the ice was already thin. Skiing in the wet snow was slow going. The men’s heavy backpacks were chafing their backs, and Saarinen broke a ski in half.

In thick fog, Jämsä and Saarinen became separated. Just before Åland, Jämsä fell through the ice. Despite their hardship, the men made it to Åland and continued their journey on from there in a rowing boat.

The adventurers survived the dangerous waves of the Sea of Åland through pure luck, and finally made it to the Swedish shore aboard a fishing vessel.

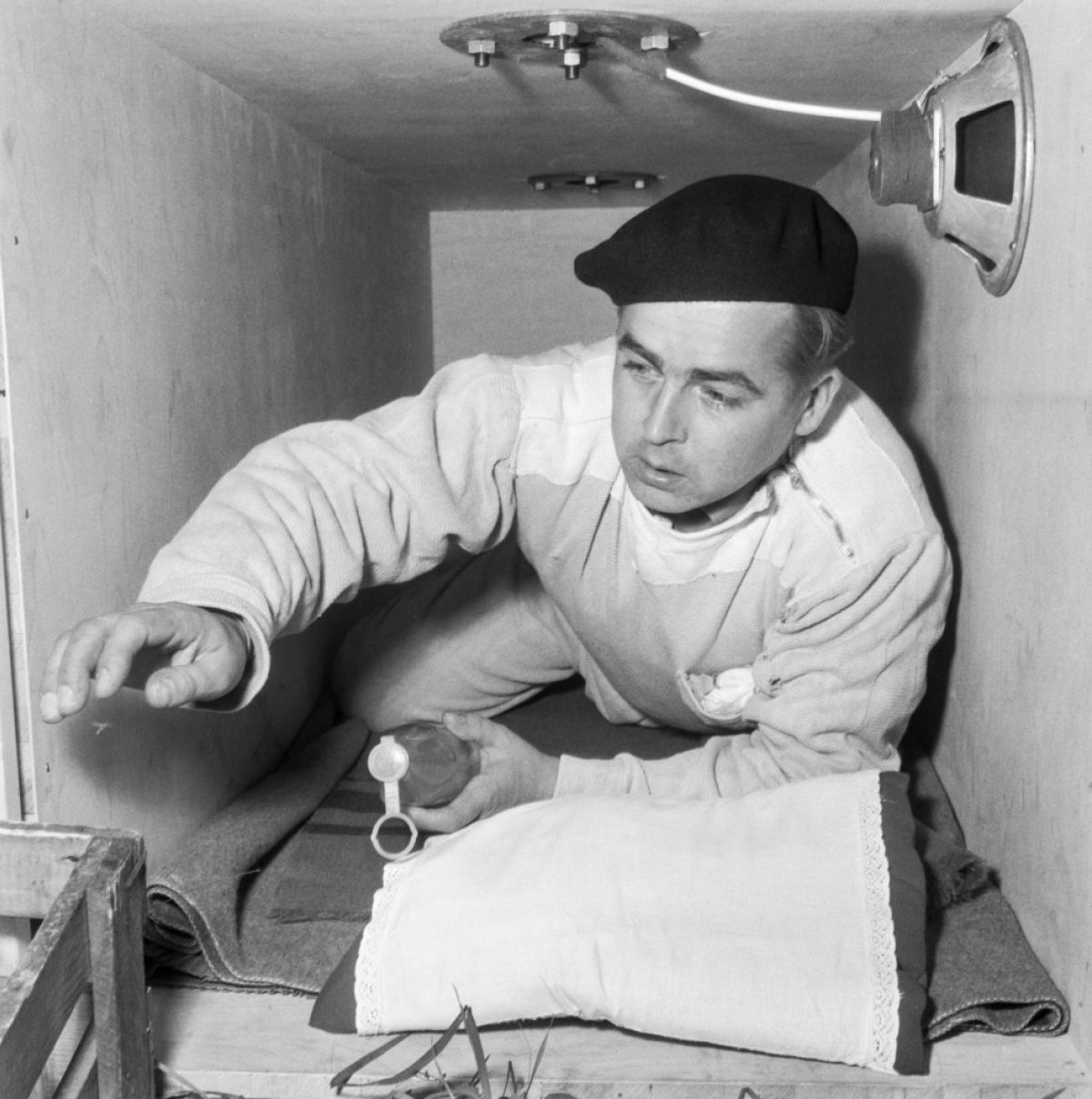

A couple of years later, Saarinen photographed Jämsä being buried alive. The magazine Apu wanted to find out whether normal people had a tendency to claustrophobia.

The experiment was also joined by fakir Jussi Pöyhönen, who had gained fame performing at Linnanmäki theme park. He suffered two claustrophobic panic attacks during the experiment, and was dug up after 22 hours. Matti Jämsä had one panic attack, but ultimately managed to stay underground just eight minutes short of 50 hours.

Jämsä became a celebrity, but soon ran out of ideas for new stunts. At the beginning of the 1960s, Jämsä changed his pen for the bottle.

Matti Jämsä is the father of Finnish gonzo journalism. A decade after him, American Hunter S. Thompson developed a first-person participatory and subjective form of journalism, gonzo, whose stylistic features included the obscuring of facts, emphasis on personal experience and exaggeration.

In Finland, Jämsä’s colleague Veikko Ennala continued his career by writing scandal-oriented gossip articles for the magazine Hymy. Others to have followed in Jämsä’s footsteps include the new millennium Dudesons, as well as Riku Rantala and Tuomas Milonoff from Madventures.

Mari Aaltonen

Kamera 1/2017

Matti Jämsä preparing to beat the Draeger DW-38 diving suit's deep diving record in 1954. Jämsä dived to 61 metres. Photo: UA Saarinen / Press Photo Archive JOKA / Finnish Heritage Agency (JOKAUAS2_3319:4)

Matti Jämsä was buried alive underneath 2.5 metres of earth in 1956. The coffin was made from plywood with two ventilation pipes attached to it. Photo: UA Saarinen / Press Archive JOKA / Finnish Heritage Agency (JOKAUAS2_3509:8)