A view into the wilds of Siberia

Kai Donner travelled to Siberia and photographed the lives of the locals with a roll film camera.

The exhibition ‘Adventures in Siberia’ of the Museum of Cultures and the Picture Collections of the Finnish Heritage Agency is on view at the National Museum of Finland.The exhibition presents photographs taken by Kai Donner, a researcher of Siberian languages and cultures, on his expeditions in 1911–1914. The first expedition in 1911–1913 was mainly directed at the Khanty Samoyed people (also known as Ostyaks) at the headwaters of the Ob River, the Yenisei River, and the Taz River. The object of the second expedition in 1914 was the tribe of Kamas Samoyeds living on the slopes of the Sayan mountains.

The Samoyeds lived in a cold, rugged area that was overrun by mosquitoes in the summer. The inhabitants were plagued with diseases, poverty, alcohol abuse and hunger. The Russian traders took advantage of the Samoyeds financially.

Donner photographed these forgotten, disregarded people. He lived among the Samoyeds and was often mistaken as a native. “Despite the harsh conditions, the way of life of the aboriginal peoples had its charm. I cannot express how much I enjoyed finally being able to be engrossed in areas that civilisation had never touched, whose ground no cultured person had ever treaded,” Donner wrote.

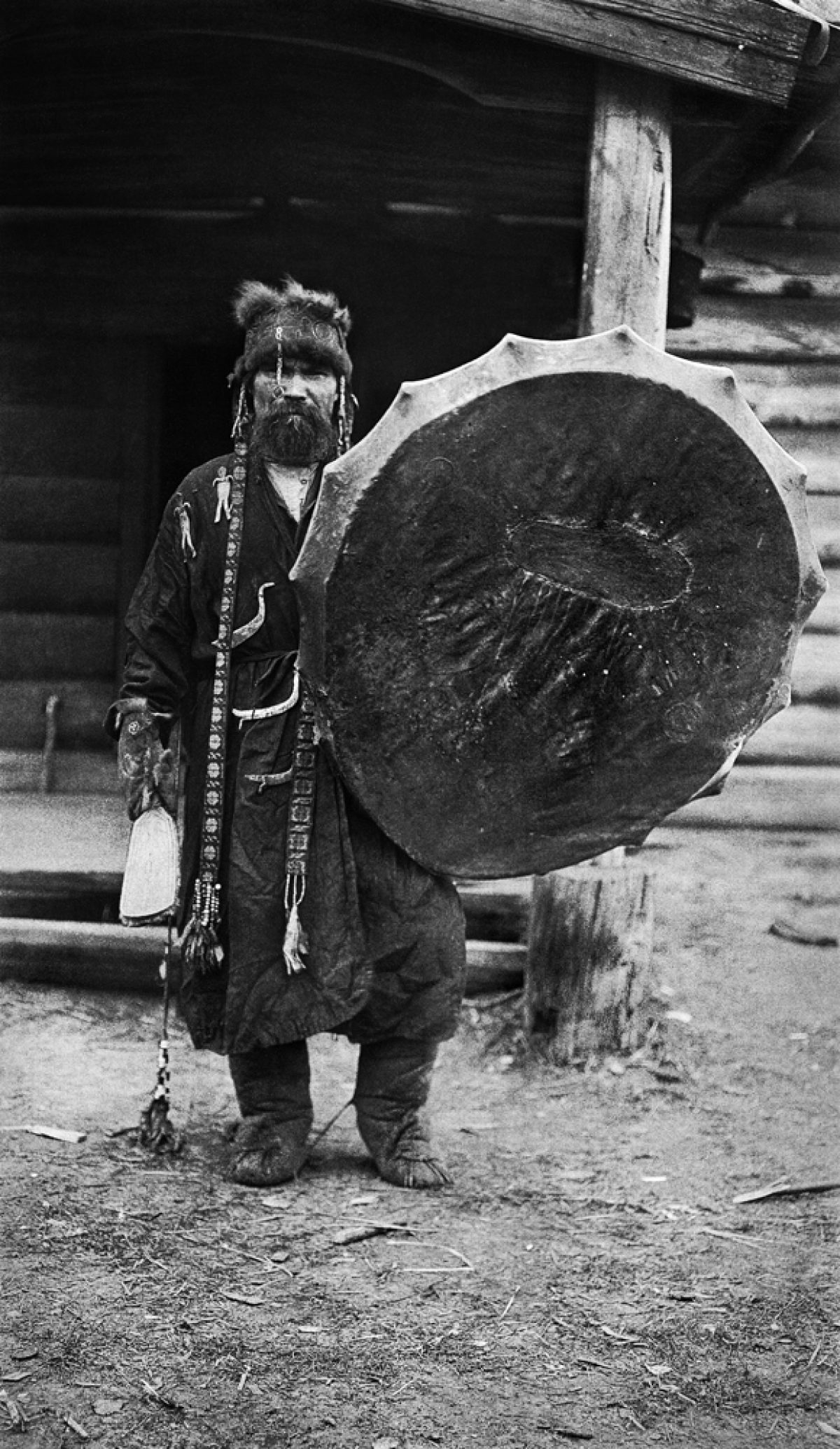

Kai Donner carried two light roll film cameras with him on the expeditions: a Bulls-Eye Kodak No. 2 and an Eastman No. 3A Folding Pocket Kodak. In cold conditions, using a roll film camera was easier than a sheet film camera. The lack of light made photography in Siberia either difficult or completely impossible. The film required a long exposure time (ISO approximately 5). It was only sensitive to blue light, which made the sky so light that the clouds disappeared. Yellow and red, on the other hand, looked darker than they were. Due to the characteristics of the film, even the colour of the Samoyeds’ skin seems darker. Most of the photographs taken by Donner are portraits. Among other things, he photographed landscapes, dwellings, Russian traders and officials, and even himself as a proof to his family that he was alive. However, people in Siberia did not always approve of the taking of photographs. The shaman Kotšijader believed that the camera contained evil spirits that might harm him. Finally, he agreed to be photographed after being convinced that the camera would only create one photograph and receiving the promise that he could keep the picture himself.

Karl (Kai) Reinhold Donner was born in Helsinki on 1 April 1888. He graduated with a Master of Arts degree in 1914 after studying at the universities of Helsinki, Budapest and Cambridge. In 1923, he was awarded the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Kai Donner’s father, the Senator Otto Donner, had wished that he could study the Samoyed tribes – this may have been one of the motives for Kai Donner’s expeditions. When he was young, Kai Donner already wanted to follow the footsteps of M. A. Castrén into the wilds of Siberia. In 1924, Kai Donner was appointed as a docent of Uralic languages at the University of Helsinki and an acting professor of phonetics starting from 1934. He died on 12 February 1935 in Helsinki.

The photographs taken by Kai Donner in Siberia are stored in the Picture Collections of the Finnish Heritage Agency.

Jaana Onatsu and Peter Sandberg

Kamera 10-11/2014

The shaman Kotšijader. Tym River, 1912. Photo: Kai Donner / Editing by Peter Sandberg / Picture Collections of the Finnish Heritage Agency (VKK532:2245)